America Invents Act impacts patent rights (MAGAZINE)

Now more than ever, innovators in the SSL sector need to move quickly to protect their LED-centric intellectual property given the AIA legislation in the US, reports MARSHALL HONEYMAN.

Let’s say your business conceived of a novel, potentially-patentable, LED-centric product a few years ago, and was considering patenting it. At that time, so long as you were reasonably diligent, you could prevail over a competitor who invented the same thing later, but beat you to the Patent Office by filing an application first. In order to overcome the filing date of your competitor, you would have been able to submit evidence of your date of conception. Assuming ample corroboration of your conception as well as the date, you could win the battle despite your failure to swiftly file to protect your intellectual property (IP). Today, the America Invents Act has devalued the luxury of time and patent activity is hectic in the solid-state lighting (SSL) arena.

Interested in more articles & announcements on LED patents & SSL design?

You may have heard of the Leahy-Smith America Invents Act, more commonly referred to as the AIA, which became effective Mar. 16, 2013. Under the AIA, any evidence you have that you conceived of an invention before a competitor will not enable you to defeat the patent of a competitor that independently invented the same thing and filed before you. The law once favored the first person to invent, but now, under the new first-to-file rules, the first inventor to file a patent application wins.

Patent law changes

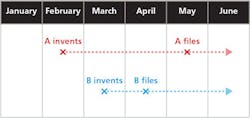

The difference is sometimes easier to understand when plotted out on a timeline (Fig. 1). The graph presumes an inventor A to have conceived of an invention Feb. 1, and then B invents the same thing a month later. Inventor B, however, as can be seen in the graph, files a patent application in the Patent Office on Apr. 1 - a full month ahead of inventor A.

Under the old first-to-invent rules, inventor A would win, assuming they could present evidence supporting conception and diligence. But under the new rules, B, as the first inventor to file, wins assuming they did not in any way derive the invention from the work of A.

Another change in the law relates to the impact of certain public activities, that, when engaged in before you file, can bar you from getting a patent. It was - and is still true - that certain public activities including sales, offers for sale, public uses, and/or publications of your invention before filing of a patent application could result in a loss of patent rights. But the bar under the old law was not immediate. You were instead given an unconditional one-year grace period to file for the patent, the clock starting with the first public activity.

The new post-AIA grace period is still a year, but it is qualified, not automatic. Disclosures made by others within the year before filing will count against you, but your own disclosures will not. For example, information independently published by third parties without any connection to the inventors could be considered as barring information and potentially invalidate your claims to a patent. On the contrary, publications, sales, or public uses made by your business or your inventors would not count. And finally, any publications made by others that derived the information from you or your inventors would not be counted against you, so long as you can prove that they derived it from you. Proving this - i.e., creating the evidentiary link required between your inventors and the third-party publication - can be extremely difficult without the benefit of a clear trail of communications.

Don’t walk to the Patent Office, run!

The takeaway from all of this is that a business should obtain a patent filing date as soon as possible. Say you have a new LED light engine. You should get a filing date before engaging in any public activities such as: demonstrating it at an upcoming trade show or anywhere else in public; publishing any information regarding the new light engine, how it works, or what it does; taking advance sales orders, or actually selling the product; talking about the new light engine with third parties without a nondisclosure agreement first being in place; or any other public activities that would disclose, or even hint at, the workings of the invention.

Immediate filing is even more important for a business targeting international markets. In most foreign countries, there is no one-year grace period. Thus, you can immediately lose most of your international rights (outside of the US) if you make it public before filing for a patent.

Ideally, it would always be a good idea to immediately file for a patent. But in reality, there are things that create delay. First, properly writing a complete patent application can be a time-consuming project - both for the inventors and for the attorney. The document requires the drafting of claims. The claims are very important, in that they ultimately define the property right in the patent. They do this by describing the invention in a very precise manner. But capturing the essence of an invention concisely depends on not only considerable communications with the inventors, but also developing a solid understanding on the state of the art. Thus, claim drafting takes considerable time. Also, special illustrations of the invention will be needed. These drawings must comply with elaborate Patent Office rules and numerous other formal components.

And it is rare that the inventors in a thriving business are able to take a drop-everything approach to the drafting process. Thus, the document can take weeks to properly draft. For many clients, it makes sense to perform patentability research before filing. Some entities conduct searches internally, but most commonly you would have patent counsel obtain a search from a professional searcher. Searches provide value in that they reveal prior art publications you did not know about beforehand, and give you an estimation of what patent coverage might be available. For example, before investing resources in pursuing a patent, the company may want to determine whether similar arrangements already exist that would limit or prevent patentability. But researching the invention also takes time away from the process of moving forward with the patent.

Provisional applications quickly get you a date

One tool that can be used to immediately establish a filing date is the provisional patent application. Provisionals, unlike the more traditional non-provisional applications, can be submitted to the Patent Office in very rough form. Provisionals can, for example, include informal sketches and/or photographs, and do not require a claims section like a regular application. The relaxation of these formalities enables swift preparation at relatively low cost. A regular application may take days or weeks to prepare, but an attorney can draft a provisional in a fraction of the time - sometimes within hours of receiving a disclosure from the inventor.

Expediency can be important when you learn, for example, that an invention is scheduled for display at a trade show. A quickie provisional can establish a filing date with little prep time so the company can spend its time getting ready for the show. Even though you have filed a provisional, you will still have to prepare a full non-provisional application for the invention. But you will be allowed a full year. This enables everyone involved to breathe easy knowing that a filing date has been established, and then prepare the full application in due course.

Defensive publications

Let’s say you’ve made a business decision not to pursue a patent. If so, you may want to immediately publish your invention - for example, on your company’s website, or using one of the online publishers such as ip.com. This is especially true when your invention is going to be plainly visible or discoverable on the ultimate product, as in the case of an LED light bar,or a light engine for a lighting array, since the invention will be easily reverse engineered. Sure, making an immediate, full public disclosure is contrary to the pre-filing secrecy plan discussed earlier. But since you are not patenting, your publication will establish it as information relevant to any later-filed patent applications made by competitors. In other words, a publication that predates a competitor’s filing date can prevent them from getting a patent on the thing. And even if they do get a patent, the publication should provide you with a good validity defense if the competitor tries to enforce the patent against you.

Publishing will not be an option where the invention is a secret that can be kept - for example, an LED encapsulating process that is undetectable in the ultimate product sold. If you can keep this encapsulating process secret, you could potentially retain exclusive use of the invention indefinitely without having to pay for patenting. Doing so, however, exposes you to the risk of a competitor getting a patent on the same process, and then using the patent to prevent you from executing the same encapsulating steps you invented in the first place, although there is a provision in the law that allows you to make a defense based on prior commercial use if you have been executing the invention in private for more than a year. It used to be that secret commercial uses were prior art. Now, under the AIA, they are not. So now, the risk of losing your freedom to operate in view of possible competitor patenting should be carefully considered before deciding to keep the invention as a secret instead of filing for a patent.

Other people’s patents

The new law also impacts how you must deal with the patents of others. Let’s say a competitor just obtained a patent that appears to cover a product your company is currently selling. This scenario is more common today than ever, considering the almost exponential increase in patent filings that has occurred over recent decades. Fig. 2 depicts that escalation, showing the patents granted per year in each of the years shown (1964, 1974, 1984, 1994, 2004, and 2014) in Class 362.

Class 362 is a class that includes many SSL arrangements incorporating LED technologies including general illumination. Thus, although the samplings are small in this class, they do accurately reflect that the patent landscape your company needs to navigate is far thicker than ever. And you would find similar escalation in other classes such as those that cover LED sources and other technologies used in SSL.

Let’s say further that you suspect the competitor’s patent is bogus and never should have been granted. What are the options? Historically, you could take any number of approaches when dealing with a likely-invalid competitor’s patent.

One approach is to do nothing. In other words, you ignore the patent and wait to see if the competitor actually attempts to enforce it against you. If your gamble pays off, then good for you. But this approach is very risky in that your decision to continue sales in the face of what might be a valid patent could result in a greatly enhanced monetary award by the court against you.

A better approach is to present the issue to patent counsel. Clients may misunderstand the scope of a given patent, but after a quick review, counsel may relieve them of any concerns that it covers the product in question. In some cases, it makes sense to obtain a written opinion from counsel of this non-infringement referred to as lack of coverage. Doing so can mitigate awards were you to be sued.

Before the AIA, the ways in which a company could challenge a patent were limited. There were reexaminations proceedings that existed, but there were associated disadvantages; thus they were rarely used.

Challenging patents

The AIA has brought forward new processes for challenging a competitor’s patent. One is a new trial process which is conducted in the Patent Office called Post-Grant Review (PGR) and is available for use against patents filed after Mar. 16, 2013. The PGR trial is overseen, and rulings are made by judges in the Patent Office. These judges can make numerous findings, including rulings on validity based on prior art not known by the examiner that formerly allowed the patent to grant. The grounds for invalidity in a PGR are many, but could include sales or publications made before the competitor’s filing date. Although bringing a PGR is expensive, sometimes costing hundreds of thousands to get to a final decision, the process is considerably less expensive than patent litigation in Federal District Court, which can cost in the millions.

Another process is called Inter Partes Review (IPR). IPR has replaced an earlier proceeding existing in the Patent Office, but has been substantially sped up and made more similar to litigation. For example, these cases allow the parties to conduct discovery - enabling the receipt of information from the other side during the process. The new version of IPR has become a viable and relatively inexpensive mechanism to challenge patents.

The frequency of use for these new processes has skyrocketed, due in part to the fact that patent challengers have had a very high success rate - much higher than exists in raising validity challenges in Federal District Court. Fig. 3 shows the total number of IPR petition filings made on a month-by-month basis. The resulting climate change has been that owners of shaky patents often hesitate to seriously threaten others with their patent for fear of losing it in a PGR or IPR.

As you can see, the IP landscape has changed considerably and understanding how the system works is critical in the burgeoning world of LEDs and SSL.

MARSHALL HONEYMAN ([email protected]) is a patent attorney for Lathrop & Gage, and is former patent examiner in the Section of the Patent Office devoted to LED, as well as other illumination technologies.