INTERVIEW | Finelite R&D executive says DfD is ‘a lot of work’ but it also expands potential for innovation

LEDs Magazine: Finelite, as a company, and you, as an R&D leader in the industry, have been vocal about design for disassembly — what that means and what to consider in terms of materials and processes. Can you run through some industry-facing initiatives and resources for DfD inspiration?

Aaron Smith: Finelite is part of some of the ongoing LCA [life cycle analysis] research projects. We're working with Pacific Northwest National Laboratory on life cycle analysis and data collection — developing tools to try and make LCA easier for the lighting industry and less expensive — and data collection; and with the GreenLight Alliance, a conglomerate of manufacturers trying to set a bar for the industry in terms of LCA for lighting fixtures across different types of product platforms. Through some of those forums, and through presenting at events like LEDucation and LightFair, we’ve received feedback that what we’ve discussed with the marketplace about DfD has value across industry and company borders.

No one organization can make an impact by itself. It takes a collective effort. We're sharing our pain points with each other and these third parties. Sometimes it means talking through a solution to a specific engineering problem or the type of supply chain that we're trying to set up so that we can get more sustainable materials. We can all leverage that knowledge.

Lighting is relatively small compared to other industries, and those other industries are moving ahead to new ways of doing things. I follow mechanical engineering blogs to see what new materials people are coming out with, and now more than ever, people are building whole factories around sustainable materials. One example is collecting ocean plastics and turning them into polymers that can be added to virgin material to offset the carbon footprint. We're looking into those types of materials. There are smart people out there working to solve material issues, not just in the lighting industry. So many places to find inspiration.

LEDs: What changes or obstacles do lighting companies need to identify and understand in order to engage in DfD?

Smith: Incorporating DfD into the culture of your product development cycle is important. You have to actively consider components early in the design phase, so that you can factor in disassembly questions and needs during the design process and educate your team. Establishing clear principles to follow going into the design process is a start.

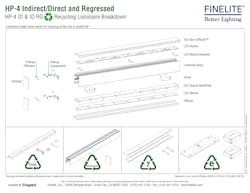

For example, when we begin product development, we’re going to make a materials list. We're going to make a fixture that will be easy to disassemble. We're going to try to limit the amount of composite materials that we're using, so at the end of life, we can recycle those materials or reuse components somehow.

Another key is pushing those ideas down to your supply chain. If we're working with driver manufacturers, how can we help them understand the need to have materials transparency for those components? That's a big pain point, trying to get material details nailed down. We ran into an issue where a potential design called for a washer and a hanging clip, and some manufacturers can't give us specifics on the materials that go into those simple components — even though they're made out of metal and steel — because they don't have traceability all the way back [to the source].

We have to work with them to understand what our need is at a basic level; and then we may even have to switch suppliers to somebody who can get us that documentation. But knowing that right in the beginning of the project, we can narrow down our options to those suppliers who can and will provide that information — examples like whether there is a composite material involved. Is it recyclable material? And so on.

LEDs: If you're trying to design a product for disassembly at end of usable life, what happens to components that need to be removed from the system because they can't be utilized?

Smith: We need more research about what happens at the end of life in a building. My experience is that it's very regional, depending on the code, the building process, or who the contractor is. There are certainly folks who have their own green initiatives; when they decommission lighting or electrical equipment, they'll separate out the components into different bins and try to get down as much as they can to the recyclable parts, especially things like copper wiring and components that are easy to separate.

Of course, there are still situations when fixtures are just getting thrown out, and you don't know what happens at the waste management facility. Are they actually separating those out, shredding them, and getting those materials out of the way? Ideally, we'd have a way of disassembling everything and being able to separate those materials so people know what they are. That's still something we need more clarity on — and this isn’t unique to lighting. It's happening everywhere.

LEDs: Does Finelite have specific initiatives that measure progress toward its sustainability and DfD goals?

Smith: For a long time, Finelite has had recyclable documentation on all of our fixtures. We've also tried to make all of our fixtures easily serviceable. We’re one of six Legrand lighting companies and Legrand has a corporate social responsibility program, and they set public targets for different sustainability goals. For example, we have goals for the amount of recycled content that we're trying to incorporate into our fixture weight as a benchmark. And we’re seeking to be carbon neutral by 2050 across the entire Legrand organization.

There is monthly reporting not only for our business sustainability but also our product development sustainability. We’re learning from each other across the different businesses what the challenges are, things like packaging and how to reduce single-use plastics, improve processes, hit new goals, and hold ourselves accountable by reporting to the marketplace — like the people who invest in Legrand. They want to see us do the right thing, and we want to do the right thing, too.

LEDs: Do you have an example of an idea from around the greater organization that resulted in a sustainable process modification for Finelite?

Smith: There is one that’s tangential to fixture design but it has everything to do with packaging and transporting end product, which can have huge carbon impact implications.

In the past, typically fixtures were put together and shipped in a box. We've developed a job pack where we ship the fixtures without a box; they can be easily stacked on a pallet. But we never had that ability with our linear fixtures, so we created a component. I don't know if you've ever ordered wine in the mail... One of our team members pointed out that they had seen wine being shipped with a molded pulp insert. It’s just paper that's in the shape of a bottle; it will allow the box to hold its shape and not collapse, and the wine will be safe. Somebody thought, what if we applied this idea to our fixtures? We could eliminate the box and use these molded pulp inserts on our pallets. The molded pulp allows separation between the fixtures and then you stack all your fixtures together on a pallet. You can eliminate so much cardboard. We can make job packs now for our 4-inch fixtures, and we're getting the tool made for our 2-inch fixtures to be able to create these job packs. Now, we can send the packs to a distributor or even to the field without using extra cardboard that just gets thrown away.

This is a good example about the level of effort that goes into coming up with sustainable solutions. With the molded pulp, we had to do a lot of testing. We’d make full pallets of fixtures and send them to a FedEx facility to compare how a regular pallet packed with fixtures fares in terms of its safety compared to a job pack. It meant utilizing our supply partners to help us and FedEx running those pallets through their paces. If they can help us, it saves them money, because they don't have orders that are getting destroyed in transit. You need that feedback… Can your pallet [stay intact through] five different transitions or two different transitions? All stuff that I never thought I would need to know, but it's impactful from a sustainability standpoint because we can ensure products get transported responsibly and not have wasted product from damage, plus unnecessary packaging.

It took a year and a half or more to get the first prototypes out, so we're probably two years into it and we're just starting to get people to use more job packs.

LEDs: How do materials sourcing and content factors influence design execution and supply-chain relationships?

Smith: This is a lot of work. Even though a material may look the same, a lot of things happened in the background to make sure that it would be suitable for our product. For example, we're looking at aluminum that has 75% recycled content versus virgin aluminum. There are tests; we have to make a new tool; and we've got to push a new extrusion with this new material and validate that it doesn't have any kind of mechanical defects, because we have to think about earthquake safety, mechanical safety, and so on. Whenever you have long spans of fixtures, especially linear, if you don't use the right material, it can sag. So you have to make sure that everything is structurally sound.

There's usually a year or two of development ahead of us being able to use that component or material in manufacturing and then deliver finished product.

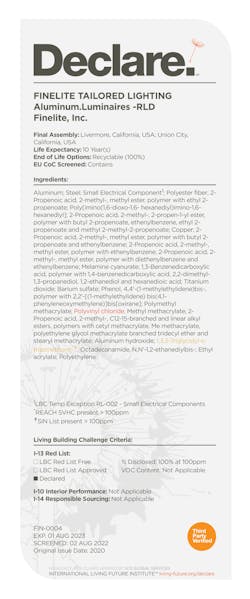

Once you find a product or material, then you ask, how do I actually get it to my supplier so that they can use it? Do I need to change suppliers? There are very commercial and practical steps that have to be addressed to be able to use a new product. Identifying the component is step one. I'm excited about it. But then funneling it to the supplier and getting them to use it, that's the next step. We have also set goals about making sure that the products are Red List Free [of specific hazardous materials and chemicals]. So, do you have all that transparency information ahead of time?

It's definitely challenging, but it's doable. The more we do it, the more this process is ingrained into us that this is the way forward; it becomes part of our culture. Always start small. Find something that's within your scope of ability to do, start working on that, and then expand from there. We didn't start with saying, "We're going to transform the whole company, every product that we make is sustainable." We're going to keep layering and building.

LEDs: Everyone asks about cost eventually. How does the transition to more sustainable materials and processes impact cost, and how has that been received by the marketplace?

Smith: Ideally it would be even — there wouldn't be a markup on a sustainable fixture. That's what we're striving toward. We have to build it into our design philosophy. When we are going out to suppliers and looking for different materials, we still need sustainable materials to come in at a very similar price to what we have now, because the market can't bear to pay more for it just because it's sustainable.

Our goal is to try to make [a sustainable fixture] as affordable as possible. Designing for disassembly has the potential to make a lighting fixture that's easier to produce, has fewer components, and has the ability to be recycled at the end of life. These simple things also make a positive impact on your manufacturing process over time. You’re not spending as much time building the fixture, so you're actually lowering your costs. Those innovations in savings could be passed along to the customer, and allow you to be more profitable and in turn have more resources to consider other sustainable processes.

Yes, some materials cost more, but processes like DfD can help offset those costs. Can you combine those [concepts] together to create something that comes in at the right price at the right time?

There are customers who are very engaged in sustainability efforts — designers and architects. Outside influences are causing them to choose more sustainable products; they know that these products might be more expensive, but they see value in those choices like having Declare labels [that identify product “ingredients”], reducing volatile chemicals in furnishings and fixtures, and they’re willing to figure out how to get those things into the project. The more they ask for it, those prices will generally start to come down.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity. It has been expanded from the initial publication in the April/May issue of LEDs Magazine.

CARRIE MEADOWS is managing editor of LEDs Magazine, with 20-plus years’ experience in business-to-business publishing across technology markets including solid-state technology manufacturing, fiberoptic communications, machine vision, lasers and photonics, and LEDs and lighting.

Follow our LinkedIn page for our latest news updates, contributed articles, and commentary, and our Facebook page for events announcements and more. You can also find us on Twitter.

Carrie Meadows | Editor-in-Chief, LEDs Magazine

Carrie Meadows has more than 20 years of experience in the publishing and media industry. She worked with the PennWell Technology Group for more than 17 years, having been part of the editorial staff at Solid State Technology, Microlithography World, Lightwave, Portable Design, CleanRooms, Laser Focus World, and Vision Systems Design before the group was acquired by current parent company Endeavor Business Media.

Meadows has received finalist recognition for LEDs Magazine in the FOLIO Eddie Awards, and has volunteered as a judge on several B2B editorial awards committees. She received a BA in English literature from Saint Anselm College, and earned thesis honors in the college's Geisel Library. Without the patience to sit down and write a book of her own, she has gladly undertaken the role of editor for the writings of friends and family.

Meadows enjoys living in the beautiful but sometimes unpredictable four seasons of the New England region, volunteering with an animal shelter, reading (of course), and walking with friends and extended "dog family" in her spare time.

![The DesignLights Consortium continues to make progress in shifting outdoor lighting products and implementation practices toward a more restrained and thoughtful strategy. [Image does not represent a DLC qualified fixture.] The DesignLights Consortium continues to make progress in shifting outdoor lighting products and implementation practices toward a more restrained and thoughtful strategy. [Image does not represent a DLC qualified fixture.]](https://img.ledsmagazine.com/files/base/ebm/leds/image/2024/08/66be810888ae93f656446f61-dreamstime_m_265700653.png?auto=format,compress&fit=&q=45&h=139&height=139&w=250&width=250)