The end of fluorescent lighting: Delegates agree to full phase-out of fluorescents at Minamata Convention

On Nov. 3, 2023, at the fifth meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Minamata Convention (COP-5) in Geneva, Switzerland, delegates from 147 countries agreed to effectively put an end to the fluorescent lighting industry. The delegates agreed to completely phase out fluorescent lighting by 2027 due to its mercury content. This decision is expected to close the loop on the manufacture, export, and import of fluorescent lighting worldwide. The agreement is also expected to accelerate the global adoption of LED lighting and increase LED lighting sales.

The Minamata Convention aims to protect human health and the environment from the adverse effects of mercury pollution. The convention is named after Minamata Bay in Japan, which was severely contaminated with mercury from industrial wastewater in the mid-1900s, leading to the illness and death of thousands of people in the area. The Minamata Convention is hosted by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).

“The decision taken at COP-5 to phase out fluorescents fulfils the renewed goal of expanding and strengthening efforts against toxic mercury pollution globally as well as CO2 emission reductions,” said Rachel Kamande, global campaign lead for the Clean Lighting Coalition, a nonprofit lighting advocacy group.

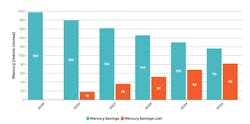

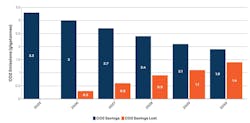

The fluorescent phase-out will eliminate 158 tons of mercury pollution and avoid 2.7 gigatons of CO2 emissions, cumulatively, from the phase-out dates to 2050, according to the appliance efficiency expert group CLASP.

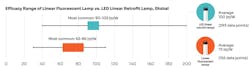

“Fluorescents use almost twice the energy that LEDs use, therefore contributing to more CO2 emissions than LEDs as energy production from coal-fired power plants leads to CO2 emissions,” Kamande said. “LEDs are the most appropriate alternatives to fluorescents because they are mercury-free and more energy efficient.”

Affected fluorescent products

COP-5 decisions primarily addressed the manufacture, export, and import of linear fluorescent lamps (LFLs) for general-purpose lighting. At COP-4 in March 2022, delegates agreed to phase out compact fluorescent lamps (CFLs) by 2025.

According to the COP-5 agreement, halophosphate phosphor LFLs less than or equal to 40W with a mercury content not exceeding 10 mg per lamp and halophosphate phosphor LFLs greater than 40W must be phased out by 2026. Tri-band phosphor LFLs less than 60W with a mercury content not exceeding 5 mg per lamp must be phased out by 2027. Tri-band phosphor LFLs greater than or equal to 60W with a mercury content not exceeding 5 mg per lamp and tri-band phosphor LFLs greater than or equal to 60W with a mercury content exceeding 5 mg per lamp must be phased out by 2027. Nonlinear fluorescent lamps (NFLs) (e.g., U-bend and circular) including all wattages of tri-band phosphor and halophosphate phosphor must be phased out by 2027 and 2026, respectively. The phase-out date bans the manufacture, import, and export of the product.

CFLs for general-purpose lighting that are greater than 30W must be phased out by 2026. CFLs with a non-integrated ballast for general-purpose lighting that are less than or equal to 30W with a mercury content not exceeding 5 mg per lamp must also be phased out by 2026.

“We are absolutely delighted that delegates at the convention shared our vision and have reached agreement on timely targeted phase-out dates for the various lamp categories,” said Gerald Strickland, secretary general of the Global Lighting Association (GLA), which was involved in discussions at the Minamata Convention.

The effective date of the ban is January 1 of the following year. So, for a 2026 phase-out date, the effective ban would start from Jan. 1, 2027.

The scope of the Minamata Convention is general-purpose lighting. Special-purpose fluorescent lamps that are used for ultraviolet light emission, such as in tanning beds and industrial processes like curing glue and paint, are not within the scope of the Minamata Convention and therefore are not affected by the decision made at COP-5.

Regional roll-out and challenges

The ban will affect all the parties to the Minamata Convention, unless a party applies for an exemption. Parties can apply for exemptions if they don’t think they are in a position to comply with the dates, but this is not a probable outcome.

“Considering that the negotiations and final decision were made to accommodate the parties’ national circumstances, and that there are available technologies such as LEDs that are widely accessible and affordable, we think it is unlikely that any party will apply for exemptions,” said Ana Maria Carreño, senior director at CLASP.

According to Carreño, many locales have already phased out CFLs and LFLs ahead of schedule. Seven states in the U.S. — including Vermont, California, Colorado, Maine, Oregon, Hawaii, and Rhode Island — have passed bills to phase out the sale of CFLs and LFLs in favor of LEDs. Implementation dates range from as early as 2023 to 2026. The European Union has already banned most fluorescent light sources, removing CFLs and LFLs from virtually all general-purpose lighting applications with implementation dates earlier this year due to the Restriction of Hazardous Substances (RoHS) directive. Pakistan and several countries in south and east Africa have announced similar measures.

Proposals to phase out fluorescent lighting at COP-4 and COP-5 were introduced by delegates from Africa. “As lighting markets in manufacturing countries shift to clean, mercury-free lighting, less-regulated markets tend to experience ‘environmental dumping’ of old fluorescent technologies,” Kamande explained. Many countries have passed or are considering policies that will ban the sale of mercury-added, inefficient lighting products in their domestic markets; however, they still allow domestic manufacture for export to less developed and emerging markets.

“Despite the fact that several countries in Africa have regional minimum energy performance standards that would effectively get rid of fluorescents, Africa is largely underregulated and has porous borders therefore at risk of this potential dumping,” Kamande said. “The Africa region has been a champion in the fight to end the fluorescent market to protect not only their own ecosystems and communities but also those across the globe.

“The real goal to phase out fluorescent lighting is because it contains mercury, a hazardous neurotoxin that is regulated by the Minamata Convention owing to its persistence in the environment once anthropogenically introduced, its ability to bioaccumulate in ecosystems, and its significant negative effects on human health and the environment,” Kamande said.

Energy, environment, and expansion of LED adoption

The agreements made at COP-4 and COP-5 ban the manufacture, import, and export of the most common types of CFLs and LFLs but not the use of these types of fluorescent lighting. End users may opt to keep their current fluorescent lighting until it burns out or otherwise malfunctions, but it would be wise — especially for managers of large facilities — to plan ahead. Linear LED tubes are available to replace old LFLs, and many are compatible with existing fluorescent ballasts, but some are not. Some users may need to install new luminaires completely, providing an opportunity to upgrade to a smart, connected LED lighting system.

Glamox, a leading lighting company based in Oslo, Norway, has seen an increase in demand for energy-efficient LED lighting systems due to the European phase-out of fluorescent lighting under the RoHS directive. Many customers are choosing connected LED lighting systems to further reduce their electricity bill or shrink their carbon footprint.

“We applaud this agreement supported by 147 nations. It’s good for public health and the planet,” said Anders Bru, business development director for RoHS and retrofit projects in Norway at Glamox. “This transition period looks sensible and the lighting industry is well-equipped to respond. However, it is important that the signatories publicize the phase-out in their countries to give enterprises and the public time to make the transition.”

“A successful, global phase-out of fluorescent lamps requires country-level renovation policies and planning to include incentive programs where installers, investors, authorities, and industry cooperate to facilitate a major transition to [smart, connected] LED fixtures and systems,” said GLA’s Strickland. “Only a united approach will ensure a smooth and harmonious implementation of the transition, particularly if market surveillance and enforcement programs are effective.

“During our involvement in discussions at the Minamata Convention in Geneva, we had the privilege of reinforcing our unwavering support for the transition,” Strickland continued. “We are truly honored to be part of this historic moment and will continue to work tirelessly towards a future where LED lighting becomes the norm, benefiting not only the environment but also the global community.”

REBEKAH MULLANEY is a freelance writer and editor with more than 20 years of experience. She has worked in public relations, marketing, and editorial roles for Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI), the Naval Nuclear Laboratory, and Albany Molecular Research. She has a B.A. in English from Kalamazoo College and an M.S. in communications from RPI.

Follow our LinkedIn page for our latest news updates, contributed articles, and commentary, and our Facebook page for events announcements and more. You can also find us on the X platform.

Rebekah Mullaney | Writer

REBEKAH MULLANEY is a freelance writer and editor with more than 20 years of experience. She has worked in public relations, marketing, and editorial roles for Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI), the Naval Nuclear Laboratory, and Albany Molecular Research. She has a B.A. in English from Kalamazoo College and an M.S. in communications from RPI.

![The DesignLights Consortium continues to make progress in shifting outdoor lighting products and implementation practices toward a more restrained and thoughtful strategy. [Image does not represent a DLC qualified fixture.] The DesignLights Consortium continues to make progress in shifting outdoor lighting products and implementation practices toward a more restrained and thoughtful strategy. [Image does not represent a DLC qualified fixture.]](https://img.ledsmagazine.com/files/base/ebm/leds/image/2024/08/66be810888ae93f656446f61-dreamstime_m_265700653.png?auto=format,compress&fit=&q=45&h=139&height=139&w=250&width=250)